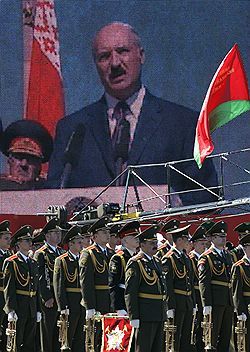

The last dictator looks to the West, but feels the power of the East

Alexander Lukashenko, President of Belarus, enjoys his own notoriety. Those are happy, he says with a smile, who happened to sit at the same table with the “last dictator of Europe.”

As a sign of complete disregard for Western political rules, the 54-year-old leader of Belarus turns this epithet into a joke. It also measured his confidence. After 14 years in office, he had almost no internal challenges, and this despite the fact that at the end of the month parliamentary elections will be held in the country.

Given the authoritarian control that he brutally established over his country, whose population is 10 million people, nothing else is possible. A decade of strong economic growth, in addition, allowed the former farm manager to gain real popularity after coming to power in 1994, after the fall of the Soviet Union. The periodic protests organized by opposition parties deprived of unity are mainly limited to Minsk.

He enjoys his control over the country. “I would be glad if you could convey a direct message to people in Europe that I have no dictatorial aspirations to stay in power, but only a huge dependence on the will of the people,” Mr Lukashenko said in an interview with the Financial Times and Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung.

The Belarusian president spoke for two hours about everything, starting with the upcoming football match between the teams of England and Belarus as part of the qualifying stage of the World Cup and ending with energy and his political creed.

Appearances to Western journalists are not unusual for Mr. Lukashenko. But times are now unusual. No matter how strong his position inside the country, he feels pressure from outside, mainly from Russia, his political sponsor, a country that provides him with economic assistance and supplies him with energy.

Long before the Georgian crisis, Mr. Lukashenko began to send signals to the West, hoping for easier isolation (including the ban on issuing visas to senior officials) imposed by the European Union after international observers condemned the 2006 presidential election as unfair.

Brussels made it clear that it was ready for some rapprochement, but only if Mr. Lukashenko made the regime less stringent. The beginning of this could be the release of political prisoners and some efforts to improve the democratic standards of parliamentary elections.

As confirmed by the EU, Alexander Lukashenko fulfilled the conditions for prisoners and took up the elections. He says he violates Belarusian laws to ensure that the elections comply with EU standards, for example, forcing election commissions to include more opposition representatives. He also invites international observers, saying: “We have opened the country to all.”

But he warns the EU and the US that they should be objective in their assessments, and accuses the West of double standards. He complains that strong countries with the same problems, especially Russia, are avoiding punishment, and says: “Whether the West likes it or not, the parliament was elected in accordance with our constitution. I won’t go ask for an EU visa.”

Mr. Lukashenko asks whether the regime’s change is the real goal of the West. He insists that he is in no hurry to leave, noting that the Queen of England has been in power for quite some time.

He says he has done a good job in his country, removing it from the post-Soviet economic mess, adding stability and raising income levels by two and a half times compared to Soviet times. According to the International Monetary Fund, economic growth last year was 8.2%, and further growth is projected to decline only slightly to 7.1% this year.

Belarus is changing, he says, but at the speed it has chosen: “If you want to change us in accordance with your standards, you can think about it, but you should not push us to this. Maybe we will come to understand that we can be 80% the same as Germany or the UK. But that should be our choice. “

Having kept state enterprises for a much longer period compared to other former communist countries, Mr. Lukashenko says that privatization is part of his plans, up to 100% of the shares are subject to sale. But, he says, the price should be fair. Investors are also invited, ready to start a new production. “Worthy” businessmen will even be given free land for their homes, “so that they live not in the backyards of Europe, as in London, but in the very center of Europe.”

The Belarusian president admitted that he irritated Russia by not recognizing the rebellious Georgian territories – South Ossetia and Abkhazia. But he does not exclude that this will be done in the future, saying that the new parliament should have its say here. He denied as an “absolutely stupid” assumption that Russian actions could be a dangerous precedent for Georgia. “God forbid Russia will try to do the same with respect to Belarus. In this unimaginable case, Europe will have every right to resist Russia uncompromisingly, by any means or leverage,” he says.

Mr Lukashenko wants the West to be more interested in the former Soviet Union. He says: Western influence has become the main reason that the former Soviet states did not follow Russia’s example regarding the recognition of Abkhazia and South Ossetia.

But where is the guarantee that the West will prove strong enough in the future to become a counterbalance to the “ever-increasing power of Russia and the growing influence of Russia in these countries”? A fair question, but not one of those that the West can easily discuss with Mr. Lukashenko.

This post is also available in:

English

English  Русский (Russian)

Русский (Russian)