Gypsies of Europe: a cool route

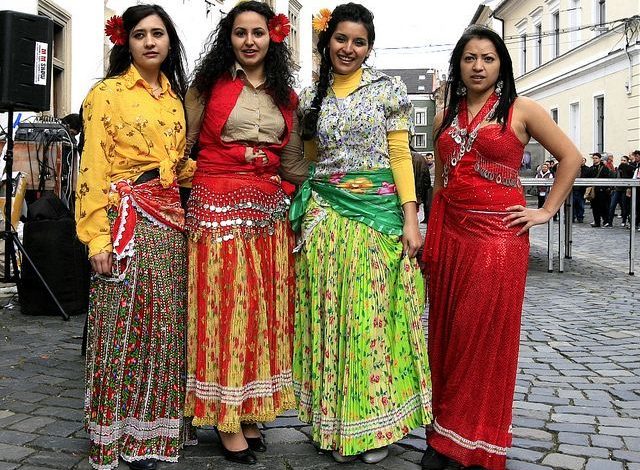

“And where do these people come from in the photographs?” – asked me the owner of the salon, where I handed over my films to print. The conversation took place in London Southall, an area with a predominantly Indian population.

“These are Romanian gypsies,” I replied. “Really? They look so much like the people of the banjar from Rajasthan, where I come from,” and the owner of the salon showed me a color shot of the graceful Indian dancers on the wall.

Gipsy musicians at the court of the Persian Shah

Historians agree that the Gypsies began their long journey to Europe from the north-west of India, somewhere between the 3rd and 7th centuries AD. The reasons for this massive migration were the same as forcing people to seek a better share in other countries today. Gypsies fled from conflict and instability, they were attracted by the possibilities of large cities – Tehran, Baghdad, and later – of Constantinople. Gypsy “migrant workers” found work in agriculture, were registered as mercenaries in the army, guards at palaces and bookkeepers.

Gypsy musicians were especially appreciated – even then. In the Arab and Persian historical chronicles one can find a legend according to which the Persian Shah Bahram Gur hired 12 thousand Indian Gypsies in the 5th century and distributed them to the cities of his kingdom so that even the poorest subjects could have fun with music.

Gypsy Kelderar in Romania. Historians suggest that gypsies became masters in working with metal back in Persia

According to the theory most widespread among historians, it was in Persia that the tribes that left India began to marry among themselves and laid the foundation for a new people – just like the African American community in North America formed from different African tribes.

Some representatives of this new nation have remained in the Middle East. They call themselves “home”, which means “man”, and speak a language close to Sanskrit. Others went to Armenia, where the “house” turned into a “scrap”, as the Armenian gypsies call themselves today. However, most gypsies continued on their way to Europe. They laid the foundation for the European branch of the gypsies, which calls itself “Roma” (plural from “rum”, all from the same “house”).

Fortunetellers, pilgrims and slaves

On the way to Europe, the Gypsies settled in Byzantium for a long time. Perhaps because these gypsies still remembered Indian traditions and gods, they were considered heretics and attributed to the sorcerer “atsigani” there. From here came the Russian word “gypsies” and the German “Zigeuner”. The church did not feel much sympathy for the gypsies who became famous in Constantinople as animal trainers and fortune-tellers, but there were no special repressions against them either.

What made the Gypsies fall off again and go on to Europe? Historians believe that perhaps they fled from the Turks, and perhaps from the plague. In addition, in Europe there was a need for working hands. In the Balkans, the nobility was glad that gypsy farmers came to their lands. In the principalities of Wallachia and Moldavia on the territory of modern Romania, gypsies enslaved the landowners and monasteries.

Some of the gypsies who left the dying Byzantium posed as pilgrims. They said that they went to wander for the atonement of sins – supposedly, they allowed the Turks to convert themselves to Islam, and now they hope to earn forgiveness. These stories were believed and given to gypsies shelter and food. However, not all gypsies seemed to be pilgrims. Historical chronicles also mention acrobats and fortune-tellers, coppersmiths, jewelers, animal trainers and sellers of animals and farmers.

Outcasts of Europe

Gypsy children are photographed, most likely, in the Rivesalt camp in southern France during the Second World War. Photo from the collection of the US Holocaust Memorial Museum

At the end of the 15th century, on the whole, the favorable attitude of Europeans towards the Gypsies was replaced by a hostile one. Historians attribute this in part to the fact that European cities no longer required such a number of labor migrants, and the church did not like that its flock resorted to the services of magicians and fortunetellers.

Gypsies were accused of all possible sins – from witchcraft to espionage in favor of Turkey. European parliaments passed anti-Gypsy laws one by one. In England, Gypsies began to be hanged and expelled from the country, in France they shaved their heads, in Moravia the gypsies were cut off their left ear, and in Bohemia – their right.

The repression forced the Gypsies to travel again, east, towards Poland, where they were somewhat more tolerant.

Gypsies were treated better in Russia at that time than in most European countries. They were not forbidden to lead a nomadic or semi-nomadic lifestyle, provided that they regularly paid taxes and taxes. In the eighteenth century, many landowners had female and male gypsy choirs, whose members subsequently moved to Moscow and St. Petersburg and laid the foundation for famous musical dynasties there.

In the era of the enlightened monarchy in Europe, the task was to make the Gypsies “civilized”. Empress of Austria-Hungary Maria Theresa and her son Joseph II set the tone for European policy regarding Roma, who were considered humane because they offered Roma civil rights, however, at the cost of not only giving up their nationality, but even their names. Under Maria Theresa, for the use of the Gypsy language, the offender was supposed to receive 24 stick blows. Gypsy children were taken away from their parents at an early age and given to foster families. Even the word “gypsies” was outlawed – instead, it was proposed to say “new villager.”

Attempts by the European monarchs to whip and stick the Gypsies with a carrot and stick have largely failed. Most gypsies remained nomads and returned to their traditional occupations.

Gypsies in the camp Belzec, Poland. Photo from the collection of the US Holocaust Memorial Museum

The culmination of repression against European Gypsies was the genocide of this people during the Second World War. Having come to power in Germany, the Nazis almost immediately declared the gypsies a racially alien element. At first they were subjected to forced sterilization, and then they began to be sent to death camps. At Auschwitz, the Nazi doctor Mengele preferred to put his genetic experiments on gypsy twins. Historians believe that during the Second World War, up to half a million Roma were exterminated.

After the end of World War II, the states on both sides of the Iron Curtain did nothing to acknowledge and help the Gypsies of Europe who survived the Holocaust. In the countries of the socialist camp, some Gypsies managed to fit into the society of the builders of communism, but only at the cost of abandoning their origin, culture and language. However, most representatives of this people and under socialism lived in extreme poverty. Communist authorities considered gypsies a social problem. In Czechoslovakia, gypsy women were subjected to forced sterilization, in Bulgaria they were forced to change their names. When communist regimes collapsed in central willow of eastern Europe in 1989, a wave of anti-Gypsy pogroms swept through these countries.

Today in Europe there are about 10 million gypsies. The largest gypsy population in Europe is Romania, where these people were kept in slavery and sold like cattle until the middle of the 19th century. The accession of Eastern European countries to the European Union has little changed in the life of their gypsy population. Still, most European gypsies live in poverty. According to international organizations, today Gypsies in Europe live 10-15 years less than representatives of other nationalities.

This post is also available in:

English

English  Русский (Russian)

Русский (Russian)