British genetic kit

The peoples gave their cultures to the Aboriginal people of foggy Albion, but disappeared into the indigenous population.

Yes, genes were common, but not culture. Painter Clyde Caldwell “Celtic Princess”.

According to recent genetic studies, the British, Scots, and Irish are almost identical in terms of their genomes. For residents of the British Isles, this discovery was a shock. All three peoples have always positioned themselves as something ethnically completely separate. Neither in language, nor in culture, nor in characteristic features, they have nothing in common with each other and are proud of that.

Brutus, the legendary grandson of Aeneas, an even more legendary participant in the Trojan War, accidentally killed his father in the hunt and was expelled from Italy, after which he ended up on a luxurious island, later named after him – Britain. He and his army gave rise to the current main population of the island – the British. So says Galfrid of Monmouth in his famous History of the Britons.

Scots, aka Scott, have a completely different origin. They appeared as a nation between the VI and XIV centuries, moving to the northern coast of foggy Albion from Ireland. And they got there, according to one version, from the Middle East.

The Irish are descendants of the Celts who settled in Ireland in the 4th century BC. Subsequently, they miraculously escaped Roman influence, and we still cherish this isolation.

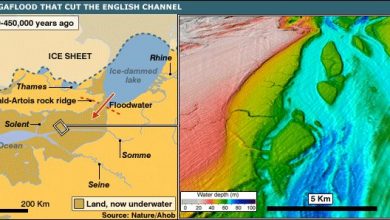

According to Stephen Oppenheimer, a medical geneticist at the University of Oxford, historical records of the origin of these three peoples lie in almost every detail. He claims that the ancestors of all these three peoples arrived on the islands from Spain about 16 thousand years ago and spoke a language close to the Basque language. At that time, the British Isles were not inhabited, because before that, for 4 thousand years, glaciers reigned there, expelling the former inhabitants to Spain and Italy. And the descendants of these ancestors make up the majority of the population of the British Isles today, taking only to a small extent the genes of the later occupiers – Celts, Romanes, Angles, Saxons, Vikings and Normans.

Yes, genes were common, but not culture. About six thousand years ago, says Dr. Oppenheimer, farming came from the Middle East to the islands – with the help of people who speak the Celtic dialect and settled Ireland and the western coast of Britain. On the eastern and southern shores, the influence of newcomers from northern Europe was stronger, they brought here a language close to Germanic, but in terms of numbers they were clearly inferior to the main population of the island.

Here’s what is interesting – both those and other aliens were too small in number and dissolved in the indigenous population of the islands, but were able to convey to the inhabitants of England their languages and their skills, completely changing their way of life.

Then these were not islands. At that time, bridge bridges existed between Ireland, Britain and the mainland, but then they disappeared due to rising sea levels, and getting there became more difficult.

According to Oppenheimer, today the genetic situation is as follows: the Irish have only 12% of the Irish genes, the inhabitants of Wales – 20% of the Welsh, the Scots can boast 30% of their Scottishness, well, the British – about the same amount of Britishness. Everything else is common. Despite the amazing difference in habits, customs, cultures and languages.

In support of his genetic research, Dr. Oppenheimer cites data from archaeologist Heinrich Hörke, according to which the Anglo-Saxon invasion in the 4th century AD added 1 to 2 million people of the islands 250 thousand newcomers, and the Norman in 1066 – no more than 10 thousand people.

This post is also available in:

English

English  Русский (Russian)

Русский (Russian)