Eurovision Joy Deflects Cares for a While

For three hours on Sunday morning, as the nightclub around him filled up with dry ice and stiletto heels, 28-year-old Ziya Rahbarli watched the gigantic screen with the gravity of a social scientist.

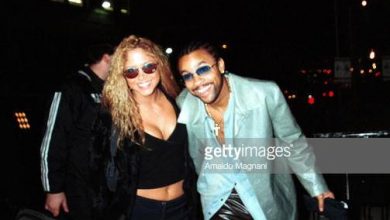

Eldar Kasimov and Nigyar Djamal of Ell / Nikki of Azerbaijan celebrated with the trophy and their national flag after winning.

His analysis of previous Eurovision Song Contests left him convinced that victory hinges on geopolitics — a subject all too familiar in Azerbaijan, a small, oil-rich nation wedged between Iran and Russia.

So Mr. Rahbarli brightened at the mention of Moldova, saying its votes might be swayed by its extensive network of Azerbaijani filling stations. He was circumspect about Georgia, whose alliance with Azerbaijan, he said, has always been tainted by envy. He racked his brain for shared ethnic roots that might sway Albania. It was not until after 3 a.m., when the vote tally showed that Azerbaijan’s singing duet had actually won, that Mr. Rahbarli’s analytical skills failed him.

“I can’t speak; I can’t speak,” he cried, gripping his head with his hands. “I am in no condition.”

Outside was a scene of mad joy. Drivers barreled through the city, leaning on their horns and flying huge flags. Those not satisfied with leaning out car windows climbed onto the roofs — or, in some cases, into the trunks — and hung on for dear life. Hummers and Land Rovers and boxy Soviet-era Ladas got so snarled on Oilmen’s Avenue, a palm-lined boulevard skirting the Caspian Sea, that everyone just got out and danced.

“We have come a very long way for this,” said Rauf Aliyev, 43, a pilot. “Europe will know us now.”

It is hard to imagine a country better prepared for the frothy burden conferred by Eurovision, a Continental battle of the bands that will now be held in Baku next spring.

Awash in wealth, Azerbaijan has developed a specialty in over-the-topness. Last Tuesday, for the birthday of the former president Heydar Aliyev, the authorities had upward of a million flowers flown in from various countries. They were fashioned into huge and elaborate sculptures, including a mosaic of the face of Mr. Aliyev, who died in 2003, made of purple, white and gold chrysanthemums. (By Saturday night, dump trucks had backed up to the park to cart away the rotting blossoms.)

Once a showcase for the whims of pre-revolutionary oil barons, Baku now boasts its own Bentley showroom and curvaceous glass towers that would look at home in Dubai. The authorities have announced plans to import a fleet of London taxicabs — in purple — at a cost of $27 million, according to the Trend news service, based in Azerbaijan. This may trump the unveiling, last year, of the world’s tallest unsupported flagpole, which measures a shade over 531 feet and cost $32 million.

For officials, these extravaganzas are a welcome distraction from social tensions that emerged this spring. Thanks to rising oil revenues, Azerbaijan’s official poverty rate dropped to 11 percent in 2010 from 45 percent in 2003, according to the International Monetary Fund. Meanwhile, much of the population lives off government allowances.

In the early morning, people celebrated in the streets of Baku, stopping their cars in the middle of the road shouting and waving national flags, after the victory of the duo of Eldar Gasimov and Nigar Jamal of Azerbaijan in the Eurovision Song Contest.

This means President Ilham H. Aliyev, who succeeded his father, “feels less incentive to pretend that Azerbaijan is a progressing democracy,” the International Crisis Group wrote last year in a report. Small antigovernment demonstrations inspired by the Arab revolutions were met with a harsh response, and many young people say they are now too afraid to participate in public dissent. But ordinary citizens do not hide their complaints about corruption and disparities in wealth.

“I don’t need Eurovision; I need money,” said Arif, 23, who did not give his last name for fear of government retribution. He said he earned about $190 a month working at a grocery.

“What will I do with Eurovision?” he said. “Our country is an oil country, but we live in poverty.”

Before dawn on Sunday, however, it felt as though all the hardships and the humiliations of the post-Soviet era had been redeemed in one swoop. As blue floodlights raked the Buta Palace nightclub, Mr. Rahbarli cheerfully recalled the competitions that Azerbaijan had traditionally dominated. It has a strong women’s volleyball team, he noted, and a legendary chess academy, and a good record on a Russian quiz show called “What? Where? When?” That was the end of his list — until now.

“For a European country, this would be a small victory,” he said. “For us, it is a supervictory!”

Within a few hours of the pop-music triumph, some Azerbaijanis were back on geopolitics — specifically, the standoff with Armenia over the enclave of Nagorno-Karabakh, an area in Azerbaijan’s southwest.

Azerbaijan has tried for years, through international mediation, to reclaim the territory from Armenian control and allow refugees to return. Ganira Pashayeva, a member of Parliament, told the Trend news service on Sunday that she hoped Nagorno-Karabakh would be the subject of the next celebration.

“I believe that this day is near,” she said.

Armenia, meanwhile, has not said whether it will attend next year’s music competition in Baku.

Amanda Erickson contributed reporting.

nytimes.com

This post is also available in:

English

English  Русский (Russian)

Русский (Russian)